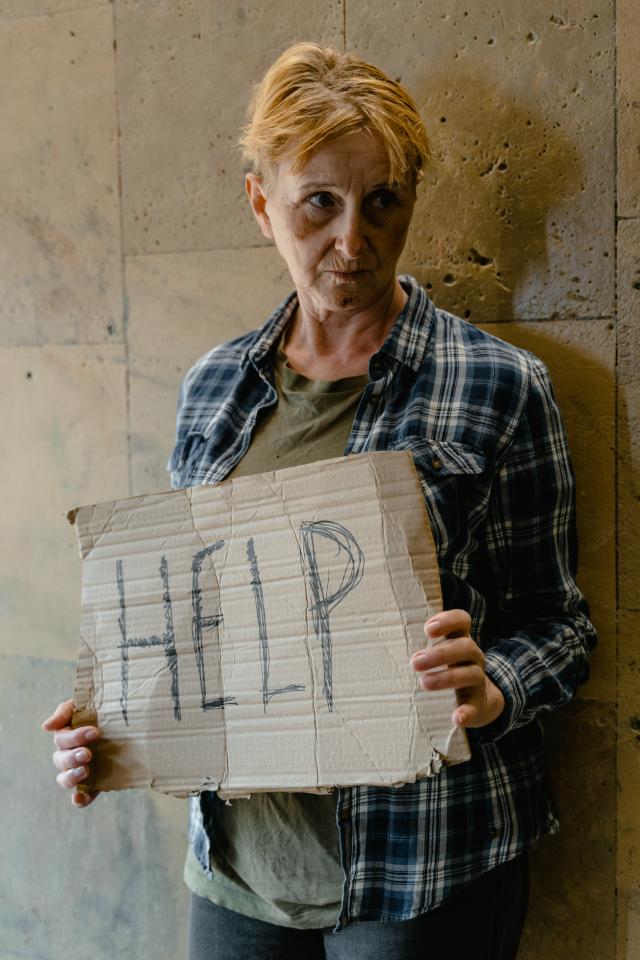

The Exacerbation of DV Amidst our Housing Crisis: Families Face Heart-Wrenching Choices

Digital Edition

Subscribe

Get an all ACCESS PASS to the News and your Digital Edition with an online subscription

Incredible artwork at Mount Morgan

In the historic gold mining town of Mount Morgan there is another gem; senior artists have joined together to create Visual Artists 4714, a...